Aligning my vision and your expectation

June 28, 2017

Does my vision align with your expectation? That’s the question I want to ask in responding to a request to speak, or to photograph, or to facilitate a meeting, or to provide coaching or instruction. Often I’m spot on, but that’s not the point. The dialog of checking in is always helpful. And creating the opportunity to be pushed toward some change is crucial.

If they don’t align, what should change? Did I not fully hear or understand you? Or, after hearing my questions and concerns, are your expectations different. At best, this is a dance, in which each of us gets a chance to lead, but we both welcome the process.

I’m writing this, having just emailed a “client” on this theme, and am feeling great that I’ve the confidence, the inquisitiveness, and the clarity to share my vision and hold it up for review.

Yes — life is a collaborative process!

My learning doesn’t stop

January 21, 2016

I’m learning with every step, becoming clearer, more curious, asking better questions that help others find more insight and clarity. Here I’ve tried to trace some of this development:

- As an undergraduate at Swarthmore College I learned to ask deep questions, to tell the truth, to be skeptical about making any assumptions, and to listen carefully to get past surface chatter.

- My scientific training (at Swarthmore and at Harvard) taught me about creating and refining models. A model is useful because it leaves almost everything out, but can be problematic for the same reason — because it leaves almost everything out. We create and evaluate imperfect models all the time, and knowing how to deconstruct them is critical.

- A summer working with the respected social scientists Robert Abelson and Philip Zimbardo on the manuscript for “Canvassing for Peace” gave me very practical experience developing strategy, testing its application on small sample sizes, responding to surprises, and implementing a revised and well grounded plan. It was also an opportunity for me to explore collaboration between academics and activists.

- Several years working with the American Friends Service Committee – first as a member of their Peace Education Staff and then as director of public relations (at AFSC this was called “Information Services”) taught me how to target and focus messages about controversial topics — keeping some edge, but building on shared values and concerns.

- Years of experience as a manager in a small rapidly growing software company, that during my tenure became a division of General Electric, taught me how to work effectively within complex organizations, collaborating with competing management segments. This job offered me a “sandbox” to learn about power, loyalty, innovation, and the importance of clearly defined mission and plan.

- Working as an independent consultant – designing and developing information systems for business and non-profit organizations,or focusing on usability and user interface – I honed my skills of listening, of change management, and of assessment and evaluation.

- Through all these years, I served on the boards of a variety of non-profit organizations – nurturing the Merriconeag Waldorf School (now called the Maine Coast Waldorf School) from a nursery and kindergarten into a K – 8 school with a million dollar building and significant organizational capacity, running a capital campaign for a Quaker study and conference center in Western Massachusetts, helping a local interfaith organization grow from a dream into a vibrant reality. I also had the opportunity to work with organizations that were seriously fractured, and learned what kinds of weaknesses most easily lead to failure, and how best to address these.

- Participation in the year long “Leadership Intensive” program offered by the Institute for Civic Leadership (now called “Lift 360”) gave me a chance to reflect on all these experiences, to explore models of collaborative facilitation and leadership, and to develop more connections within the greater Portland business and non-profit community.

- As a consultant to non-profits, I’ve honed my skills at facilitation, strategic planning, coaching, questioning, collaborating, and leading workshops and retreats.

- For three years, I was Recording Clerk of the New England Yearly Meeting of Friends – taking minutes of week long gatherings at which as many as 500 Quakers from around New England conducted the society’s business. My task was to listen and record, with each formal minute approved as the meeting progressed. Often it was my job to suggest a minute that reflected the unity we had found, but also the matters that still required more work together. I was considered part of the session leadership, but viewed my role as a servant task. I found my gift of helping a community find its voice — both the voice of its agreement, but also of the discord or lack of clarity. It’s a gift to be able to articulate clearly the points of our disagreement.

- I’m a great listener, a reconciler, and a creative force skilled in consensus-based approaches. I was one of the authors of book chapter on the process of Quaker decision making, and have often been called upon to help divergent groups work together. Working within complex organizations, I know how to formulate great questions, and draft talking points that will help others facilitate constructive change.

- I’ve another life as a photographer of dance. While this might not appear to be parallel to the other experiences listed above, I do believe that deep engagement in a creative process – where even with best efforts things don’t always proceed as expected or as planned, and where agility can be as important as mastery – offers many lessons that are surprisingly applicable.

When asked what should be included in an Executive Director’s report to the board, I responded with this model of “OARS” to help the board be aware of the steering environment:

- O = Opportunities . . . that the organization can (and perhaps should) pursue

- A = Accomplishments . . . both little and big successes

- R = Risk factors . . . things that look like they might go wrong, including action taken to mitigate these.

- S = Surprises . . . that the ED encountered. Yes — even in a well run organization, with very professional staff, there are surprises

This model was inspired by the “Significant events” report I had file each week when I was a mid-level manager at General Electric. Each of my staff had to write such a report to me, and I distilled and condensed these, along with my own list, in my report to senior management. Our “significant events” were named differently, but functioned in the same way to alert our managers about situations that would likely develop — either into more mature problems, or into inspiring successes.

The underlying value here is truth telling. I knew it was easy for my staff to report great successes, or opportunities that seemed to be developing. It was much harder to report those out of control situations that could get worse, those stakeholders whose dismay was escalating, those situations that seemed only to work against us. But my job was to know of such situations, and to organize appropriate responses. Were I kept in the dark, I couldn’t really do my job.

Tell me a story, about …

September 11, 2013

The best way to shares our lives. or visions, our dreams, our fears . . . is by telling stories. And one of the best ways to do the same things about our organizations (profit or non-profit) is to tell stories. Opening ourselves to a story telling mindset is very adaptive.

Recently I was mentoring somebody who was very conflicted about whether to proceed on a certain path. He wasn’t clear that he wanted to reach that destination, and was equally unclear whether the words associated with the celebration of that path were words he could say with integrity.

I was in no position to offer advice. I couldn’t know which direction was preferable, and, besides, i was his “mentor” but not his guide. it would have been appropriate for me to even try to chart his course.

But I could offer the following process:

- Tell me a story about following that path and where it takes you.

- Then, tell me another story about standing back, and not following that path. Where does that leave you?

Note that neither of these were requests to analyze, measure, or weigh. He’d done that a lot already, and that process only added to the inner conflict. Instead, I was asking him to let stories flow — and, indeed, they did.

It quickly became clear that the words associated with the certification were a crucial concern. The destination might have been right, but the words were an obstacle.

Again, story telling was the way forward. I asked him to create a story of a certification process that had resonance, with words he could easily say and stand behind. Then, I suggested, he might explore how much freedom he would have to use his words and his process.

I never heard that story, and don’t know exactly what pathway opened up. But he was able to follow a solid path to that destination, and I do know that he found the clarity he sought.

Did it matter that I never heard the inward part of this story? Not at all! Some stories are meant to guide us, and not to inform the rest of the world.

The same kinds of stories can guide non-profit organization and even for-profit corporations as they plan program, product lines, service offerings, etc. I recall vividly one occasion where I was asked to help re-design some software — following guidelines that intuitively seemed quite wrong to me. I spent several days watching their staff using the current software as they talked on the phone with their customers or clients, and listening to both sides of each phone call. Finally I was able to blurt out a very simple version of what seemed like the iconic story behind each interaction. The staff was thrilled to hear it stated so simply, and found that the story we had exposed led directly to a greatly improved and simplified version of the software.

As I look forward to each dialog with a client or prospect, with a non-profit board member or concerned stakeholder, with a troubled director or an engaged staff member, the five words that are almost always at the tip of my tongue are, “Tell me a story, about . . .”

Exploring Secular Sense of the Meeting

December 12, 2012

I’ll be offering this week long workshop at the week long “Friends General Conference” gathering this summer. But I’d love to work with anybody about how Quaker-ish process might work in any secular setting.

“We’ll explore ways in which something akin to a Quakerlike process can be used for secular decision making, and how it brings clarity and community to the life of non-profit organizations and even to for-profit companies. What’s left of Quaker process without it’s emphasis on spiritual discernment? Come and find out!”

Organizational styles — In process!

October 26, 2012

I’ve been aware of much work on personal communication styles — how we each can best receive support, advice, criticism, support, validation, etc. And, of course, there are various personality models that help us understand all these things.

But I’m aware of much less work characterizing organizations. Thus I set about to put together this simple model. I present it here as something in process, for discussion and validation only. Please add your commentary. And if you’rereading this through another blog or medium (such as a LinkedIn group discussion), please make sure that you post here any comments that you post there as well .

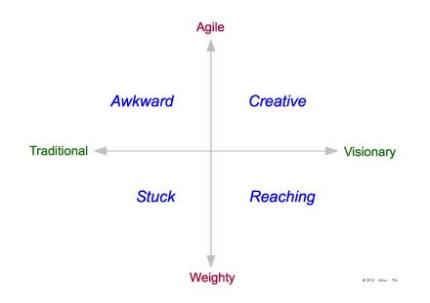

I characterize organizations along two dimensions:

Traditional . . . Visionary

Weighty . . . Agile

And the, for each quadrant, I’ve assigned a name:

A traditional organization, that has some agility but not vision, is Awkward.

A traditional organization, that is more weighty than agile, ia probably Stuck.

A visionary organization, that remains weighty, is truly Reaching.

And, finally, an organization that is both visionary and truly agile is truly Creative.

Although I suggest that this characterization is for organizations, it may better fit organizational segments, perhaps a department or work group.

How helpful is this model? Are the quadrant names appropriate and helpful? And how useful is this picture to you? Please comment.

What’s the real problem?

October 12, 2012

How often we try to solve a problem in the terms first presented to us. Occasionally this works. But very often the statement of the problem is self-limiting, and tends to steer us away from finding a real solution. Or — and this is just as problematic — we may re–phrase a problem in limiting and perhaps misleading terms.

Not long ago I changed the e-mail address at which I receive notices from what had been a very active mailing list. Instantly, I noticed that incoming mail from that list had stopped. What was going on? Was there a spam filter? I realized that I’d changed the list settings before creating my new email account. Had the list sent mail to the momentarily non-existent email address, and then turned me off? What other scenarios could lead to such an email blockage. I worked diligently on this problem, sought the assistance of the list owner and of several list participants, but got nowhere. A whole weekend went by, but no solution appeared.

And then the email I wanted started to flow. It turned out that this once-active list had experienced a significant decline in traffic, and there had been absolutely no messages during the whole weekend. Come Monday there was a trickle of emails on the list — and they all came through to me just as they were supposed to.

In fact I had originally seen the problem as, “No emails coming through”. But then I had quickly rephrased it into a question that I thought would be more helpful — “What is blocking my emails?” And holding on to that paradigm had blinded me to the very simple solution — “There were no emails for anybody”.

Recently a colleague shared with me her concerns about the board of the small nonprofit that she directs. We immediately began talking about various training programs or board retreats that might make the board a more functional support for this nonprofit and for its director. It felt appropriate for us to talk about the possible agenda for such training, whether it should be for all board members or just those on the executive committee, etc. Our unspoken paradigm was that the board didn’t understand its best role, and so wasn’t behaving in the most productive manner. Bring about the required understanding or attitude and the problem would be fixed, we believed.

It took quite a while for us to step back and reformulate the problem, into the simple statement, that “The board is not serving the role needed by the organization and its director”. And with this understanding we could ask whether, in fact, the right people were serving on the board, whether the personal benefits they sought from board service were consistent with the organization’s situation, and whether there were any positive models of board service within the board’s recent history. Board training (in the conventional sense) remained one possible option, but not the only option.

Another organization that I’ve worked with found that they weren’t taken seriously when seeking large contributions. They struggled to produce clearer descriptions of their programs, that they were sure would excite potential major donors. The new materials were better, and did attract more small donations. But they didn’t solve the problem — major donors were still holding back. It turned out that the public financial statements were unclear and inadequate. This didn’t bother small contributors, but were a real concern to major donors. A new treasurer was able to produce much clearer financial reports, and larger contributions began to flow.

In each of these cases the relevant people heard a statement of the visible problem, but made assumptions as they translated it into a limiting reformulation. Letting go of those assumptions and asking anew what was the real problem turned out to be the key.

The moral here is simple: Our first question should always be, “What is the problem?”. And we need to answer that in the most primitive way, trying to state the problem as seen or experienced, rather than as transformed by some suggestive but often inaccurate assumptions or deductions.

Workshop design: Crucial Questions

September 18, 2012

I’m just beginning to design two new “Skillbuilders” (workshops) for the Maine Association of nonprofits. Workshop design comes easy to me, and I’ve a track record of considerable success. Still, I’m expecting to learn significant lessons as we first experience these workshops being presented to live audiences. How can I maximize my learning from these pilot runs? And how can I organize my initial work so that these questions are clear?

My first rule is to always list the goals, and design the evaluation process, before completing the workshop design itself. Just the titles, in this case “Asking Great Questions” and “Crafting Your Elevator Speech”, are not enough.

For example, digging deeper into my “Asking Great Questions” agenda, I began to see such questions as:

• Who should be learning what about the process of creating, editing, and asking questions? (Who is our target audience?)

• What key ideas or understanding do we believe participants in the skillbuilder should take away? (What are we aiming to teach?)

• What experiences (not what lessons) will have make this happen?

• Are there important things that participants may need to un-learn? (What habits, or what blindness, are we trying to overcome?)

Working with such questions early in the workshop conception stage, I began to see that the kinds of questions that might fit into an employment interview are very different from those that we might want to ask of other stakeholders in our organization, of lawmakers or regulatory officials, of teachers or of researchers and guides whom we trust.

With each clarification of the goals comes new clarity about how to observe and measure whether we have achieved those goals. And, so, the evaluation process is built as the workshop is designed. Even more important, the questioning process informs the whole conception of the workshop.

In fact, I needed to create another set of questions, to evaluate my initial description of the Skillbuilder, before even developing the main workshop agenda:

• Who will the description attract, and are these the people I want in this skillbuilder?

• What expectations will the description create, and is this an expectation that I can and want to fulfill?

• The skillbuilder will be require very active participation, and will include little content that can be received passively. Will that be clear and a positive aspect of participant’s experience (or will there be comments about the lack of Powerpoint slides with detailed text guides)?

Thinking about this process led me to look back at the first outline I wrote for an earlier Skillbuilder I had developed with Deb Nelson. Along with my first rough draft outline, I had sent her a memo with a heading “Questions for Us”, and the following content:

• Our goals for the workshop

• What we have to tell or teach vs. participants learning from each other

• How we will know we have succeeded — Key evaluation question

• Possible pitfalls — What should not happen?

• Personal goals — Why we are doing this

Ask yourself these and similar questions as you prepare your presentations, your lectures, your workshops. Even when the answers seem to be obvious and so clear, write them down. Revise that draft copy. And let your questions be your guide.

My best mistake (!)

September 6, 2012

Does something sound wrong with this title? Most of us want to trumpet our successes, and hide our mistakes. And yet it’s through important mistakes that we can learn the most important lessons.

With this thought in mind, here’s my “best” mistake. Mark (no, not his real name) had hired me before, as a consultant with two of his companies. And now he was CEO of an interesting multi-division firm, with lots of appeal. He brought me in first to rework systems in a smaller division, and then to work on the major corporate systems. I was doing a great job (or so I thought), even though I was running into resistance. Projects that create change always incite some resistance, so this was not a concern. But then Mark left the firm.

All of the sudden, I was alone, really reporting to nobody. Nobody owned the project that Mark had created. And, not surprisingly, I was asked to leave as well. It wasn’t because of my work, or my results. I was just an orphan, and nobody was a stakeholder in my success there.

What did I learn from this? Well, no longer after he left, Mark referred me to another firm, whose CEO, Peter, was a friend of his. Again, it was the CEO who wanted to hire me, and I was instrumental in his plans to bring the organization to another level. But I didn’t want to repeat the same boom and bust scenario again. So, this is what I set in place:

I insisted that Peter form a management team, to take supervisory responsibility for my work.

Each month, before I arrived for a week of week, they would set the agenda, identify goals, and develop detailed plans to insure that I was given the needed resources.

Then, after I finished my week of work, they would meet and review the results.

My work was valued, and so there were often conflicts about which projects were given to me. I could deflect all of these, pointing to the management team that was setting the agenda.

In short, I created a place for Arthur Fink the consultant in their management chart — even though I was never a full time (or even part time) employee. And even when Peter became the target of criticism for some of his decisions (or lack of decisions), I was well insulated from this political stuff.

Business, and the work of non-profit organizations, is all about relationships. But when your position of tied to one possibly frail connection based on one relationshp, everything is at risk. By creating groups or communities, and establishing relationships with them, one can be better informed and much better protected.

Ten Traits of a Great Consultant + Eight More

September 5, 2012

Any consultant wanting to hone his or her skills should read this recent article by Bernard Ross and Sudeshna Mukherjee in The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

Here are the ten points they list: (For a detailed explanation, read the article!)

Following this list, I’ve added eight more that I believe are at least as important.

* Have self-confidence and be as adept at delivering bad news as good.

* Have a good understanding of the business and of themselves.

* Have transferable skills.

* Have the ability to simplify and explain a problem.

* Have more than one solution to a problem.

* Be a good listener.

* Be a team player.

* Be able to market.

* Gain client trust.

* Remember who’s the star.

And while I agree strongly with all of these, there are more traits that I believe are equally important:

* Be comfortable telling the truth. Clients may just want to hear positive words, expressions of praise. A great consultant is willing to say what needs to be said.

* Be tactful and affirming. Truthtelling doesn’t need to be negative and abrasive. A great consultant can phrase criticism as helpful suggestions, and can lead the client toward constructive action.

* Know how to ask great questions. Great consultants ask great questions. It’s through such questions that we learn what’s really going on, what the client thinks is going on, and what different groups within the client organization think is going on.

* Be willing to play together. You can learn only so much sitting at the conference table. Spending some quality time with the client outside of the office environment is important as well. A great consultant can engage the client in different venues, and, by so doing, learn much ore about motivations, hopes, fears, etc.

* Have lots of integrity. Confidences need to be respected. Promises need to be kept. A great consultant only makes promises that he or she can and will keep.

* Admit mistakes. Great consultants aren’t always right. What’s important is that they take responsibility for the advice they offer, and are willing to acknowledge when it proves to be “off” in any way.

* Love simplicity. Even when Business and organization problems seem quite complex, some simple models will help clients understand. A great consultant and report and prescribe in very simple terms, but will still be ready to address the added complexity that may be part of a full understanding.

* Enjoy the work. Great consultants have fun. Working with clients can be like playing in a sandbox, and helping clients solve their own problems can be like building those sand castles most of used used to create as children. Clients will catch on — that it’s fund to learn, to develop new understanding, to think up new possible solutions, to test ideas, and to work together in a collaborative environment.

It’s all about Spirit

January 10, 2012

Jodi Flynn (of Luma Coaching) and I have been meeting to share our understanding of the coaching process, of how to facilitate constructive change, and of how we ourselves have gotten more “on track”.

The agenda for our most recent intensive was, “How do I know my goals and actions are in alignment with my authentic self, or my authentic path?” Business coach Mandy Schumaker had posted this question, and we both felt that it was an important starting point for any transformative process.

Jodi was well prepared, with a brilliant list of “red light” and “green light” indicators, that could help us identify when we’re on or off that path. Read her blog entry for more about this very helpful set of questions, and how they might be applied.

What I want to report here concerns that “ah ha” moment, when one of us exclaimed, “It’s all about Spirit”. Both of us have had the experience of feeling actions, writing, images coming through us rather than from us, so it should not have been surprising to hear this affirmation of personal faith.

But what followed was much more radical. I asked Jodi whether this applies to all her clients, and not just those who consider themselves believers of some sort. Without hesitation, Jodi replied, “Absolutely!” She explained that the words may be different, God or Christ or Buddha language may not fit, but that sense that we all connect with some higher power not under our conscious control is primary and universal. It can be a challenge to acknowledge this truth, while not proselytizing a particular expression of it, but we both affirmed that this is possible and necessary.

“What about clients who have much more mundane concerns?”, I asked. “How can I be more effective at work, more engaged in home life, more successful in promoting my own business?” Again, Jodi’s clear response, with which I concur, was that to access our greatest potential we have to look within and whether we acknowledge it or not, that is the process of accessing spirit.

“Spirit” may not be the right word for you, if it bring up old baggage, negative experiences with religion, dogma with which you disagree. Perhaps you’ve a better word for that guiding force, that source, that positive constructive energy that can lead us towards centered grounded action. And your coaching work may appear to stay far from notions of spirit or whatever. But the affirmation that came out of our sharing was that Spirit really is at the center.

Opening ourselves (and others) to change

December 3, 2011

I recently met with Jodi Flynn (of Luma Coaching) to explore the basis of our coaching work — and that meant talking about how to catalyze change. Thanks to Jodi for much of the content I’ve included in this short post.

Most of us (and so most of our clients), are change averse. Even when we can imagine or understand the benefits of some change in our lives, our organizations, or our relationships, something holds us back. As coaches, we want to open our clients to constructive change. What helps this happen?

We shared several models:

- Comparative pain: We may help our clients realize or understand that the real pain of the status quo is greater than the imagined pain of the change they may be contemplating.

- Pain, perseverance, and gain: Every change involves pain. Things seem harder to do at first, or situations are more awkward. This lasts for a period of perseverance, but then we’re no longer held back. And — the real benefit — after a while there’s a gain over where we were at the beginning. Helping clients acknowledge this rhythm, and project the actual pain, perseverance, and gain, may open them to change. Also, it may be possible to find strategies that control the amount of pain, the or the perseverance period required.

- Fear may increase when we look it in the face. By painting a detailed model of the life we want, the way we want to work, the quality of a relationship, or whatever is the desired subject of change, the positive vision can become so compelling that resistance to change begins to diminish.

- We may not look for change in the parts of our lives that we experience as fixed. In other words, we may not name the need for change until the possibility of change feels real. I offered the example of a married couple, who might declare, “Well, we get along okay.” Seeing no alternative to their current lives, they accept when seems immobile. But upon visiting a marriage counselor, and finding ways to identify issues and work with them, they may revise their assessment to “We never realized how problematic or empty our relationship was!”.

- Empowerment may be the key. When we experience ourselves as the victim of circumstance, as conflicted because of the woes of our lives, as powerless to change our situation, we’ve little energy to invest in change. When we can experience ourselves as responsible, as in a synergistic relationship with the world around us, we become empowered to change our situation. And even though some outside circumstances of our lives may really be fixed and not easily changeable, we can change the way we carry ourselves and relate to that fixed world. So … helping clients understand how they can choose that relationship can open them to change. Jodi spoke of a model leading us from being victim to just being in conflict, then being responsible, becoming of service, acting in reconciliation, existing in synergy, and finally becoming non-judgmental so that we can act much more easily on our own behalf instead of in reaction to the provocation of others or of circumstances. Being able to place ourselves in this spectrum helps us become open to change.

Whether we seek to improve our personal lives, become more effective within their work organizations. develop teams and groups that can better create solutions to social or business problems, nourish relationships or simply build confidence, change is required. How we embrace change, or transform our resistance to it, determines how we will succeed. And understanding models, such as those I’ve shared above, is key to helping people make that transformation.

Blog posts such as this often invite just minor comments of appreciation or disagreement. But I do hope that this one will start a more vital discussion. What has helped you overcome your resistance to change? And how might coaching, counseling, or other assistance have helped in that process?

Some questions for a nonprofit board to consider (even before you hire a consultant)

October 12, 2011

As I work with non-profit boards, these are some of the questions I usually raise. But you can use these on your own. I’d welcome feedback about which are most important, which need to be changed, and what should have been included but was not.

Mission / Vision: Does the organization have a clear mission statement, and a vision of what it seeks to achieve? At what point in time might the mission be accomplished? When has the board last revisited mission and vision? Are staff, board, and executive aligned on mission and vision? Are mission and vision statements referenced when program ideas, and internal policies are being considered? Does the board notice when stated mission and actual function are different, and can it take constructive action?

Stakeholders: Who are the stakeholders, or potential stakeholders? How does the board connect with or represent the stakeholders? If some stakeholders are not in some way represented on the board, how does the organization maintain ties with them? To what groups does the organization feel itself accountable?

Board membership: How are Board members chosen? Does the board include people with experience to evaluate and clarify the organization’s need for legal services, accounting, publicity, marketing, program development, fundraising human resources, etc.? Is the board primarily a policy-making body, or does it seek is it a “working board” (providing some of these services)? Are there term limits for board members? How does the board identify and cultivate new members with the right skills, experience connections, and commitment? Is there a training protocol for new board members, and a regular check in with continuing board members as they get re-appointed?

Board meetings: Are board meetings well attended lively events, that engage the board and that result in useful dialog and decisions? Do board members come away excited and involved? Is there a clear agenda, with board questions presented in enough detail and accompanied with enough background material? Are meetings run in a manner that encourage candid sharing, creative problem solving, and the generation of consensus whenever possible? Is the board able to listen carefully to minority views, to see how these might provide helpful insights and guidance? Are minutes taken carefully, and then reviewed by the board? Read the rest of this entry »

When faced with an interesting problem, some consultants may start by offering advice — usually well seasoned advice. That’s not my style. I prefer to ask questions that define an agenda, that help the participants find their own insight and clarity.

So, when preparing to take part in a meeting of entrepreneurs who might be growing their solo business into a firm with two or more employees (perhaps many more than two!), I prepared the following twelve questions:

Note that I do offer some comments after each question, but these do not attempt to suggest what the answer should be.

1. What’s the core product or service, and how will it get refined / expanded /replaced as the company grows?

[If the plan is for you to do that yourself, think more about delegating.]

2. What are your key strengths, and, most important, your key weaknesses.

[The later should define your hiring priorities.]

3. What the company “brand“?

[And, if there isn’t one, how will it get established? (Note that the brand is not just the product or service you offer, or a statement of its advantages.]

Gift certificate shopping spree

April 18, 2011

I have several coaching clients who are dutiful in helping others, but hold back nurturing themselves. Whether it’s a tool that that really need (and would use well) or a massage or special meal that might help them celebrate, guilt or other forces keep them from offering these gifts to themselves. Even naming the things they might want can be difficult.

One way I’ve found to make get past this is to ask my coaching clients to create a set of gift certificates for things / services / experiences they want. For example, “I’d never get a massage, but it sure would be nice to have a gift certificate for one.”

The homework assignment is to generate those 12 or 20 gift certificates. This puts it right on the table. My clients may or may not cash in their fake gift certificates, but they have the experience of being much closer to taking something that they really feel would be positive, and, in so doing, to be nurturing themselves.